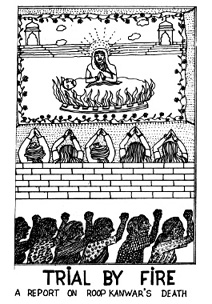

Cover illustration designed by Shakuntala Kullkarni for Trial by Fire, a publication of the Women and Media Comittee of the Bombay Union of Journalists.

In 1987, in the Indian village of Deorala, Roop Kanwar, a cosmopolitan, educated 18 year old burned to death on her husband's funeral pyre.1 This event raised tremendous controversy in India and in the West. Anti-sati feminists responded with protests and marches, condemning the glorification of sati, yet they barely influenced the 300,000 pilgrims who came by the busloads to worship at the site of the cremation. The devotees not only paid homage but also created a perfect commercial setting for selling sati by buying cheap reproductions of the couple's wedding portrait, taking tour's of Kanwar's bedroom, and bringing business to the many sati memorabilia stands that had suddenly cropped up all over Deorala.2