Tara and the Tantric Body

Thanks to JLA Online Mall for this original artwork.

by Tara Knowland

The Tantric Body

Why do we talk about the Tantric body? Focusing primarily on The Cult of Tara by Stephen Beyer, we will see how the body figures into the rituals which he describes in great detail. The body and its elements are important in these so-called rituals. This designation of the Tantric body is, in fact, partly arbitrarily assigned by me. Nonetheless, there is no denying that the body is meaningful here. Body is both something and nothing. It is merely a construction of a self and an awareness that do not exist. At the same time, the body and its elements are important instruments in attaining enlightenment.

Miranda Shaw writes, "The pioneers of the Tantric movement . . . believed that sensual pleasures, cultivated and refined through metaphysical insight, are the mind's portal to the transcendent bliss of supreme enlightenment."1 It is, then, perception and insight into the true nature of those ecstatic and sensual experiences (which are so present in Vajrayana, or Tantric, Buddhism) that afford humans the chance for enlightenment. Moreover, that with which we are most familiar (including the most mundane to the most sensual experiences) which can act as a, nay, the vehicle of enlightenment. Certainly, then, the body and its senses are essential to that experience, as a vehicle.

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

We will further examine how the body comes into play in the rituals of Tantra in the sections on Meditation and Mandala and Tara. But first I want to examine basic bodily elements and their functions and general importance in Tantra:

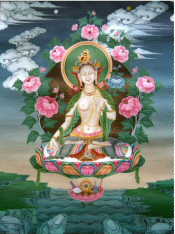

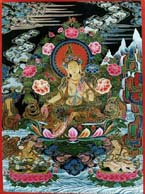

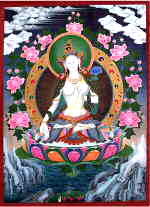

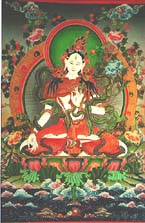

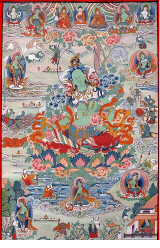

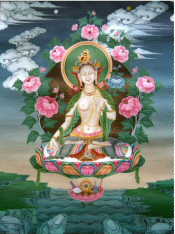

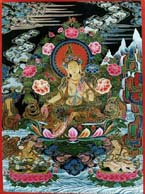

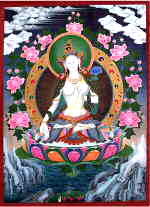

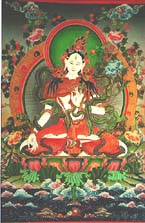

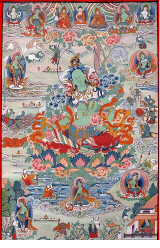

We see on this web page many examples of art depicting the goddess Tara. This art is an interesting example of the manifestation and importance of body in Tantra. The prescribed visualizations (which we shall discuss at length in the section on Meditation and Mandala) result in a total image, extremely detailed and vivid. (You can click on many of the images to seem them in greater detail). What these pictures show is that, even though the paintings of White Tara, for example, are different in some ways, they share basic characteristics in the depiction of Tara's body, which are important. For example, White Tara has seven eyes. This symbolizes "the vigilance of her compassion."2 This bodily feature is important -- it is a part of not only her outward appearance but moreover her enlightened state and her characteristics.

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

Body, then, can say a lot about a person (or a deity, as the case may be). Beyer describes the ways in which different elements of the body aid in determining how long before one will die. Presumably, the more time one has left, the more time one has to become enlightened. The cycle of birth and death (samsara) begins again if one is unable to attain enlightenment in the here and how, which is the goal of Tantra.3 Thus, death is something to be feared and avoided. Beyer says, "The Tibetans are constantly aware of the fragility of man's hold on life, and this awareness has led to the formulation of an entire science of death, the interpretation of the signs of decay of life and the creation of rituals to deal with its causes."4 Beyer then goes on to cite examples from the Bardo t'ordo text of the six classes of signs: external, internal, distant, near and miscellaneous.5 All of these signs are either directly of indirectly linked to the body, its form and its elements.6

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

Tantra is famously identified with sex in the Western world. From the time of colonization when the missionaries and colonizers saw it as immoral and attempted to suppress it to the present day when stars like Sting have made Tantric sex all the rage. It seems to me, though, that this misses the fundamental point of Tantra. Sex is not for its own use. John Blofeld writes, "The energy of passions and desires must be yoked, not wasted. Every act of body, speech and mind, every circumstance, every sensation, every dream can be turned to good account."7 Sex, then, is not the only component of Tantric body and ritual. Miranda Shaw, as we saw above, sees it as a matter of ecstasy -- these are the only instances by which we are able to being to return to the "blissful source and ground of being." These instances include not only sexual encounter but also, "the joy of embodiment . . ., loss of self in rhythmic dance, artistic creativity and the abundant richness of taste, touch, smell, sound and sight." And it is because of this believe that the body plays such a critical part in Tantric ritual.8

Meditation and Mandala

The meditation that is part of ritual is largely part of "[t]he Process of Generation [which] is a sequence of contemplative events that produce a divine body; both the body and the events are simulcra for the magical control of a wide range of realities."9 Again, we see here that the process is not merely for its own sake: rather it is both for the power resulting from it which allows for magical function, "the employment of divine power,"10 and as a means to attaining enlightenment, ". . . all figures and images evoked in the mind in this mediation are, after all, only meant, as the words, vestures and gestures in a ritual, to suggest feeling, to provoke states of consciousness . . ."11 which may lead to enlightenment.

Tantric meditation incorporates the body, speech and mind12 in various ways, particularly through hand gestures,13 the utterance of syllables and visualization. These methods are used particularly because there comes a point when tangible thought ceases and esoteric thought begins. Blofeld writes, "Tantric Buddhism is a science of dynamic mind control which produces levels of consciousness deeper than conceptual thought. In describing those levels, words fail; in experiences them, logical thought is transcendent -- hence the need for symbols."14

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

There is also a more codified association. For example, certain syllables are associated with certain body parts, as Beyer says, the "signs of Buddhahood." Certain verses associate different body parts such as thighs, breast, neck, and cheeks with different syllables such as I, R, L, and E.15 And not only are certain syllables identified with specific body parts, the syllables in general are associated with the meditative process. One example is the Process of Perfection (which takes place during the conclusion of the process of self-generation in a specific ritual), quoted by Beyer: "The vowels and consonants with five-colored light, radiate forth from my right nostril, bearing on their tips the deity of the three circles of the mandala; the purity of the triple world and make it into their own essence; and the entire world -- now the same as those dakas and yoginis, innately divine -- enters through my left nostril and reaches the level of my navel."16 And so the association with the body in meditation occurs on several different levels. This makes the connection between the practitioner, the practice and the deity all the stronger.

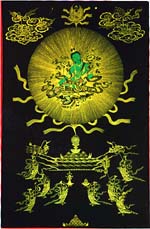

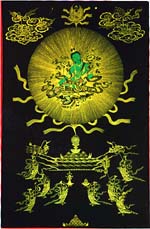

We see here two examples of Green Tara mandalas. Mandala is an important part of the ritual and as well as part of meditation in general. The visualized mandala may be offered up to the deity.17 The body can also be a mandala -- when the practitioner visualizes the body as a divine mansion. Beyer quotes a ritual of Guhyasmaja which involves the body mandala: "Before and behind my body, to the right and left, are the four sides of the mandala; my mouth and nose, anus and penis, are the four gates . . ."18 The practitioner continues to visualize and construct the body mandala and to array the deities in it. It is, again, we see, the incoroporation of the body, which brings mandala and meditation directly in contact with the practitioner, allowing him to have contact with the deities and to self-generate as one himself. This more direct contact, this experience of ecstasy (as Miranda Shaw might put it), allows for a deeping understanding, leading to enlightenment.

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

Tara: Body and Ritual

So, incorporating the elements we discussed above, the Tantric body and meditation and mandala, we arrive at their application in the Cult of Tara as discussed by Stephen Beyer. From the beginning, Tara seems to have been linked to body. Beyer tells the story of Tara's enlightenment. It is said that she, having reached enlightenment, was told to wish that she might have the body of a man. She knew, though, that the gender constructions were (as discussed above) merely constructions of non-existent reality. So she wished instead, "'. . . may I, until this world is emptied out, serve the aim of beings with nothing but the body of a woman.'"19 This act, betraying her compassion in her desire to become a Bodhisattva and help others, is important because it shows that the body is simultaneously something and nothing. It does this by showing that the body is merely a construction at the same time as being of importance in aiding and attaining enlightenment.

So, incorporating the elements we discussed above, the Tantric body and meditation and mandala, we arrive at their application in the Cult of Tara as discussed by Stephen Beyer. From the beginning, Tara seems to have been linked to body. Beyer tells the story of Tara's enlightenment. It is said that she, having reached enlightenment, was told to wish that she might have the body of a man. She knew, though, that the gender constructions were (as discussed above) merely constructions of non-existent reality. So she wished instead, "'. . . may I, until this world is emptied out, serve the aim of beings with nothing but the body of a woman.'"19 This act, betraying her compassion in her desire to become a Bodhisattva and help others, is important because it shows that the body is simultaneously something and nothing. It does this by showing that the body is merely a construction at the same time as being of importance in aiding and attaining enlightenment.

Tara's form is also important in visualization. Her body is vividly envisioned in many different rituals. Beyer quotes Nagarjuna describing Green Tara, "The single face of the Chief Lady is the understanding of all events as a single knowledge. The green color of her body is power in all functions. Her two hands are the understanding of the two truths: her right hand the conventional truth, her left hand the absolute truth. Her right foot stretched out is the abandonment of all the defects of all qualities . . .,"20 and the text continues, connecting the body of Tara to various qualities. The visualization of Tara as well as self-generation as Tara lends itself to the enlightenment process. Body, again, brings the practitioner to the ecstatic experience that is the connection to bliss.21

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

Furthermore, we see her importance in self-generation, which is best illustrated by quoting a ritual, as given by Beyer:

"All becomes Emptiness. From the realm of Emptiness is PAM and from that a lotus; from A is the circle of a moon, above which my own innate mind is a white syllable TAM. Light radiates forth therefrom, makes offerings to the Noble Ones, serves the aim of beings, and is gathered back in, whereupon my mind the syllable is transformed, and I myself become the holy Cintacakra: her body is colored white as an autumn moon, clear as a stainless crystal gem, radiating light; she has one face, two hands, three eyes; she has the youth of sixteen years; her right hand makes the gift-bestowing gesture, and with the thumb and ring finger of her left hand she holds over her heart the stalk of a lotus flower, its petals on the level of her ear, her gesture symbolizing the Buddhas of the three times, a division into three from a single root, taking the form of an open flower in the middle, a fruit on the right, and a new shoot on the left; her hair is dark blue bound up at the back of her neck with long tresses hanging down; her breasts are full; she is adorned with divers precious ornaments; her blouse is of varicolored silk, and her lower robes are of red silk; the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet each have an eye, making up the seven eyes of knowledge; she sits straight and firm upon the circle of the moon, her legs crossed in the diamond posture."23

Dharmapala Centre -

School of Thangka Painting.

The description is vivid. We understand the visualization created to look something like the picture shown here. I think, as I have said before, that this vivid visualization is necessary to create a strong bond between deity and practitioner. In self-generating himself, all of himself, as Tara, he takes on her ego as well as her body.24 This allows him to see the world, the universe, non-reality from a different perspective. If he truly takes on the ego of the deity, it allows him to view everything outside the construct created by his own body and the preconstructions and preconditions that accompany body, particularly gender.

Conclusion

We have seen various ways that the body is important in Tantrism. The visualization of the deity allows for connection to the deity. The self-generation process allows for an even closer connection to the deity because the practitioner becomes the deity. The practitioner experiencing, as a deity, the ecstasy of enlightenment. Various elements of the body are important in ritual. Moreover, these elements of the body are important to the mindfulness of oneself and one's state of consciousness in everyday life.

Tantric Buddhism is such that it cannot be separated from body. While this fact caused much of the Western world to look down on it for quite some time, it, in fact, makes a lot of sense. James George, in his review of Miranda Shaw's Passionate Enlightenment, writes that the most important point is that "tantra is not about sex, but about all the energies that constitute a human being, male or female, in their complementaries and paradoxes."22 So, then, body, as the site of that energy, much be important: it must be the Tantric body.

Many thanks to the fantastic people at the Dharmapala Centre - School of Thangka Painting for all of their paintings, including the one used for the background. Please visit their wonderful web site to see more artwork and to get information about them!

Bibliography

Comments, questions and suggestions are welcome. taknowland@vassar.edu

So, incorporating the elements we discussed above, the Tantric body and meditation and mandala, we arrive at their application in the Cult of Tara as discussed by Stephen Beyer. From the beginning, Tara seems to have been linked to body. Beyer tells the story of Tara's enlightenment. It is said that she, having reached enlightenment, was told to wish that she might have the body of a man. She knew, though, that the gender constructions were (as discussed above) merely constructions of non-existent reality. So she wished instead, "'. . . may I, until this world is emptied out, serve the aim of beings with nothing but the body of a woman.'"19 This act, betraying her compassion in her desire to become a Bodhisattva and help others, is important because it shows that the body is simultaneously something and nothing. It does this by showing that the body is merely a construction at the same time as being of importance in aiding and attaining enlightenment.

So, incorporating the elements we discussed above, the Tantric body and meditation and mandala, we arrive at their application in the Cult of Tara as discussed by Stephen Beyer. From the beginning, Tara seems to have been linked to body. Beyer tells the story of Tara's enlightenment. It is said that she, having reached enlightenment, was told to wish that she might have the body of a man. She knew, though, that the gender constructions were (as discussed above) merely constructions of non-existent reality. So she wished instead, "'. . . may I, until this world is emptied out, serve the aim of beings with nothing but the body of a woman.'"19 This act, betraying her compassion in her desire to become a Bodhisattva and help others, is important because it shows that the body is simultaneously something and nothing. It does this by showing that the body is merely a construction at the same time as being of importance in aiding and attaining enlightenment.